Coverage and Structure of the Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe

Contents

- Focus and main aims [this page]

- Culture across space: “Europe” and its “Cultural Communities”

- Culture over time: the Romantic Century and its “Cultural Currents”

- ERNiE’s Person-Related Articles and Thematic Articles

Focus

ERNiE studies Romantic Nationalism as the celebration of the nation (so defined in its language, history and cultural character) as an inspiring ideal for artistic and intellectual expression; and the instrumentalization of that expression in politicla consciousness-raising.

The celebrations, definitions, inspirations, expressions and instrumentalizations involved in Romantic Nationalism are traced by the Encyclopedia in three dimensions: in space, time, and cultural praxis; that is to say: across Europe, across the “long nineteenth century” and across the different media and fields of cultural life.

Main aims

1: An operational understanding of culture in national movements

ERNiE aims to thematize the notion of culture in the historical study of national movements and nationalism. It aims to bridge the existing gap between modernists, who tend to disregard culture as an inconsequential pastime or as an inert ambience, and traditionalists, who tend to reify culture anachronistically as a transhistorical defining essence.

In its application to ERNiE, “Culture” has a wide application, including

- artistic production and re-production,

- knowledge production, and

- cultural reflection

.“Culture” is nevertheless applied specifically and analytically, not as the catch-all phrase that it sometimes becomes in colloquial usage.

- Culture should not be trivialized to just a set of ingrained behavioral habits; nor should it be a euphemism for what (for good reasons) one does not quite dare to call a “national identity”. In the sense as used here, culture is a focused, self-aware, productive social praxis with social and political agency. As such, culture is a topic for historical analysis rather than a framework for it.

- ERNiE does not provide general culture-historical overviews of the various nationalities of Europe.

- Nor does ERNiE’s cultural coverage include important public concerns such as religion, politics or the physical environment (landscape, urban development) – these are referred to only insofar as they elicited national-cultural reflection.

2: Against methodological nationalism

Culture is communicative, and unlike social or political activism can broadcast its contents far beyond its location and moment of origin. Many social or political studies of national movements necessarily concentrate on the specific locations or societies where the relevant activities, literally, “take place”. Since culture does not “take place”, it tends to be marginalized in the analysis. This in turn exacerbates the risk of single-nation tunnel-vision. That risk is a given since most archives and historical institutions tend to be organized a priori on a country-by-country mono-national basis. This inbuilt gravitation towards methodological nationalism in nationalism studies necessitates a comparative, transnational counterweight. A focus on culture’s historical dynamics serves as such. It reminds us that the nation is, if not “constructed”, then at least hotly negotiated and (re-)articulated; and it helps us to remain aware of the communicative, transnational and cross-cultural interactions that rendered nationalism such a transnational phenomenon.

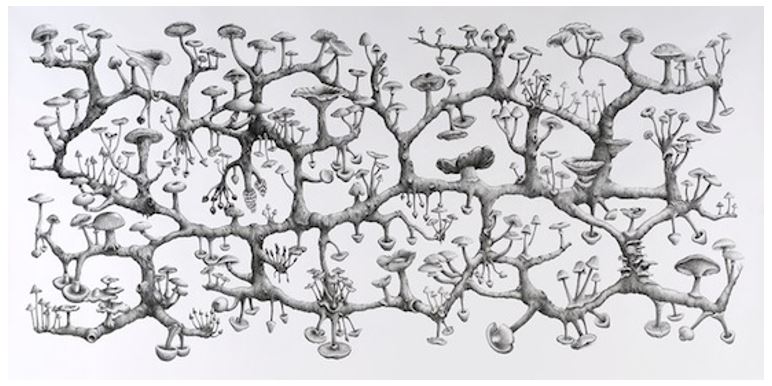

In studying mushrooms, one needs to take account of their underground connective tissue (mycelium) and their windborne spores, not just the separate toadstools.