Coverage and Structure of the Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe

Contents

- Focus and main aims

- Culture across space: “Europe” and its “Cultural Communities”

- Culture over time: the Romantic Century and its “Cultural Currents”

- ERNiE’s Person-Related Articles and Thematic Articles

The Romantic Century [*]

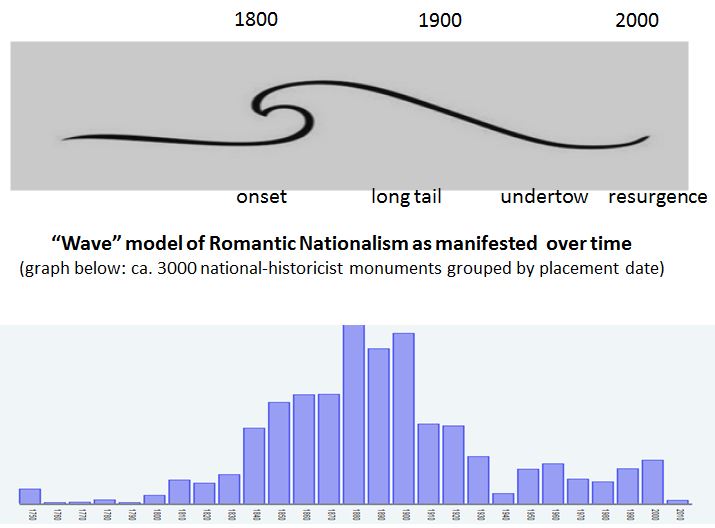

The manifestations of cultural nationalism in Europe coincide closely with the rise and fortunes of the Romantic movement in the arts: a sudden onset around 1800, a heyday between 1810 and 1840 followed by a tapering decline as counter-movements (Realism, Positivism) make their presence felt, a revival in the fin-de-siècle, a long afterlife in the 20th century as an undercurrent in high modernism, and a second wave in the end decades of the 20th century. As the materials in ERNiE demonstrate, the chronological curve of Romantic Nationalism (as measured by number of production instances ordered by production date) resembles a wave.

This means that the “long nineteenth century” (1789-1914) which forms the time-scale of our analysis is asymmetrical: marked incisively by a paradigm shift at the start, and gradually tapering off at the end.

The onset

The beginning is marked by the coinciding effects of a number of simultaneous revolutionary moments.

- In constitutional thought: the notion of popular sovereignty

- In technology: the automatized production affecting book printing, cheap paper manufacture (woodpulp)

- In state organization: the rise of new-style state-instituted universities, central archives and national libraries, all with professional staff

- In science and linguistics: the rise of the comparative-historical methods, the Indo-European paradigm

- In philosophy: the rise of post-Kantian idealism and dialectics

- In the arts: the dominant importance of non-cerebral inspiration and intuition

The cumulative effects of these innovations led to the rise of medievalism (in philology, in the historical novel and in history painting) and of folklore studies, to a new way of history-writing (at once archive-based and nation-oriented), to new “Romantic” (pathos-driven, idealizing) schools of poetry, music and painting.

In this cultural climate, nations came to be redefined as transgenerational kin-groups maintaining a cultural inheritance (language, laws, memories, narratives) over time in what was now called their “Volksgeist”; and intellectual and artists gained symbolical prestige as being the foremost spokespersons of their nation.

The long tail

The latter end of the long 19th century does not mark the actual demise or desuetude of either Romanticism or Romantic Nationalism, but rather their submergence in a new climate. Romanticism was overlaid by the aesthetics of technologically inspired, experimental art (that Modernism which positioned itself as anti-idyllic, anti-sentimental, anti-rustic and anti-nostalgic – in short: anti-Romantic). Romantic Nationalism, following the Paris Peace Treaties of 1919, was submerged into anti-individualistic political thought and a drift towards collectivist, authoritarian or totalitarian politics. Even so, its traces remained present and active, diffused into what can be called “banal nationalism” out of which Romantic Nationalism re-emerged as an operative force in politics after the Cold War.

[*] The periodization is explained in greater detail in the Introduction to ERNiE’s book version and here.