World Fairs and International Exhibitions: National self-profiling in an internationalist context, 1851-1940

Amsterdam, 8-9 March 2018 (in collaboration with Eric Storm, University of Leiden)

Click here for full programme.

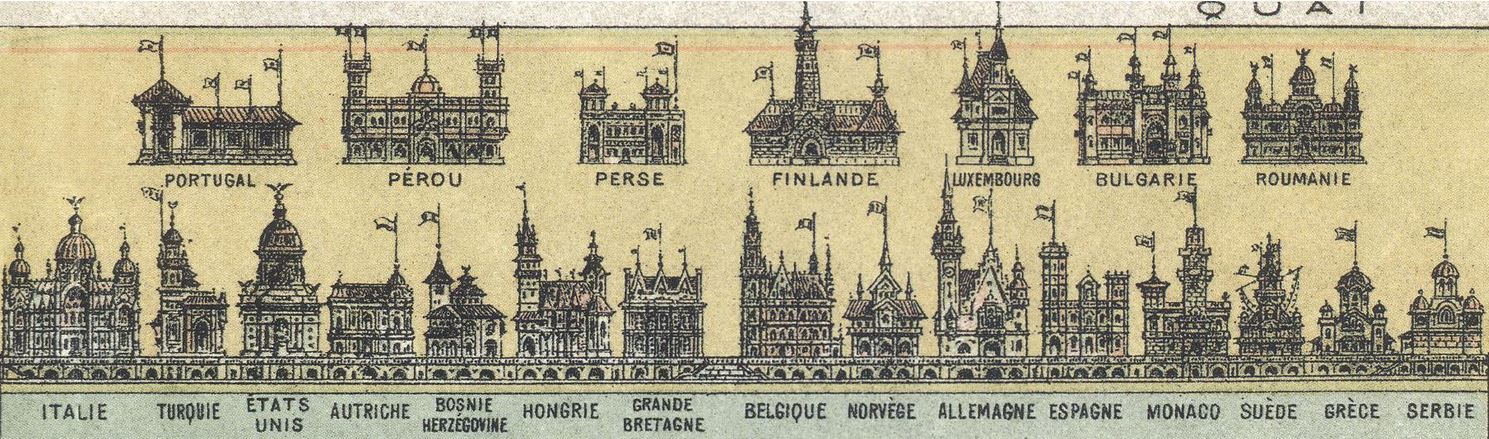

Probably the most important global stage for learning how to represent a national identity was the world fair. These grandiose international exhibitions emerged during the decades of post-1848 nationalism – which also saw the rise of mass tourism – and formed part of the panoramatic “spectacle of modernity” that dominated all mass-oriented representations of landscapes and societies in these decades. At the first Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851 all participating countries had their own section in London’s Crystal Palace to show their contribution to human progress. However, it was difficult to be distinctive with machines, inventions and fine arts, which look quite similar everywhere. Therefore, at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867 each participating country was invited to also erect a pavilion in a characteristic national style to exhibit its own “authentic” culture. These national pavilions became an integral part of subsequent international exhibitions, and world fairs became an international platform for showcasing a country’s distinctive characteristics.

World fairs were held on all continents, visited by millions of people, received extensive coverage in the international press and had myriad national and regional offshoots (Wesemael 2001; Greenhalgh 2011; Geppert 2013; Filipová 2015). Various authors have already made clear that world fairs were part of a larger “exhibitionary complex” (Bennett 1988; Stocklund 1994), where networks of professionals codified “a standard repertoire” (Geppert 2013). World fairs imposed their own modalities of representation on any participating country, be they dynastic states, heterogeneous empires, emerging nation-states, colonies as represented in imperialist-eurocentric “colonial exhibitions” or ex-colonies emerging as new nation-states. Thus, world fairs became – among many other things – the main global stage to represent national identities. After the 1940-1945 caesura their functions were gradually replaced by trade fairs, theme parks, and new visual media.

The national identity of the participating countries was displayed in terms of design, architecture, crafts, traditional costumes, music, dance, dishes and beverages. Since national pavilions were juxtaposed in the same section of the exhibition grounds they competed for the audience’s favour. This provided a strong incentive to construct pavilions that were distinguishable, recognisable and attractive, while intensifying the search at home for those building blocks that would highlight the nation’s specific character.

The present exploratory workshop – which will be held on 8 and 9 March 2018 in Amsterdam – is intended to map the resulting strategies of representation as a set of cultural conventions and as a set of strategy-choices for the participating countries. To which extent do world fairs play into a specific sub-type of nationalism, noticeably arising in the 1890s, that asserts both the nation’s traditional cultural specificity and, by demonstrating its participation in cosmopolitan, progressive modernity, and its autonomous viability?

The selection of speakers and conference programme have been finalized, but auditors are welcome. More info from SPIN@uva.nl. .

For more information: Eric Storm (h.j.storm@hum.leidenuniv.nl) or Joep Leerssen (SPIN@uva.nl).

Benedict, B. 1991. ‘International Exhibitions and National Identity’, Anthropology Today 7/3, 5-9.

Bennett, T. 1988. ‘The Exhibitionary Complex’, New Formations 4, 73-102.

Çelik, Z. 1992. Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-Century World’s Fairs, Berkeley: UCP.

Corbey, R. 1993. ‘Ethnographic Showcases, 1870-1939’, Cultural Anthropology, 338-369.

Filipová, M. (ed.) 2015. Cultures of International Exhibitions 1840-1940: Great Exhibitions in the Margins, Farnham: Ashgate.

Geppert, A.C.T. 2013. Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Greenhalgh, P. 2011. Fair World: A History of World’s Fairs and Expositions from London to Shanghai 1851-2010, Winterbourne: Papadakis.

Hoffenberg, P. 2001. An Empire on Display: English, Indian and Australian Exhibitions from the Chrystal Palace to the Great War, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jong, A. de. 2001. De dirigenten van de herinnering. Musealisering en nationalisering van de volkscultuur in Nederland 1815-1940, Nijmegen, SUN.

Mitchell, T. 1989. ‘The World as Exhibition’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 217-236.

Qureshi, S. 2011. Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Chicago UP.

Rydell, R. 1984. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916, Chicago UP.

Stocklund, B. 1994. ‘The Role of the International Exhibitions in the Construction of National Cultures in the 19th Century’, Ethnologia Europaea 24, 35-44.

Storm, E. 2010, The Culture of Regionalism: Art, Architecture and International Exhibitions in France, Germany and Spain, 1890-1939, Manchester UP.

Wesemael, P. van 2001. Architecture of Instruction and Delight: A Socio-Historical Analysis of the World Exhibitions as a Didactic Phenomenon (1789-1851-1970), Rotterdam: 010.

Wörner, W. 1999. Vergnügen und Belehrung. Volkskultur auf den Weltausstellungen, 1851-1900, Münster: Waxmann.

Wyss, B. 2010. Die Pariser Weltausstellung 1889: Bilder von der Globalisierung, Berlin: Insel.